Louise Bourgeois: Along came a spider

I came from a family of repairers. The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it.

This learning resource engages primary and secondary students with Maman 1999 by Louise Bourgeois, a monumental sculpture on display in the forecourt of the Art Gallery of New South Wales as part of the exhibition Louise Bourgeois: Has the Day Invaded the Night or Has the Night Invaded the Day?

This resource is designed to inspire art-making, critical thinking and discussion about one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. It focuses on a reoccurring theme in Bourgeois’s practice – the spider.

-

How to use this resource

Use this resource in the classroom, in preparation for the Big Art Day program Louise Bourgeois: Along came a spider for primary students, or in conjunction with a visit to the exhibition Louise Bourgeois: Has the Day Invaded the Night or Has the Night Invaded the Day? at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

In this resource you will find images of artworks from the exhibition, artist quotes, artwork wall labels, curator audio and curriculum-based strategies for making and responding.

Included case studies

Analysis of Louise Bourgeois’s Maman 1999

Related works from the exhibition that reference spiders

K–6 questions and activities encourage students to identify, discuss and experiment with different techniques, media and variations of form, line and colour to gain an understanding of Bourgeois’s art. These making and responding ideas help students to connect the artworks to their own world.

7–12 questions and activities are designed to support student analysis of Bourgeois’s artworks using the frames and conceptual framework. These prompts encourage critical thinking about the artist’s practice and the relationships between the artist, artworks and audiences, as well as the world in which they were created.

-

Who is Louise Bourgeois?

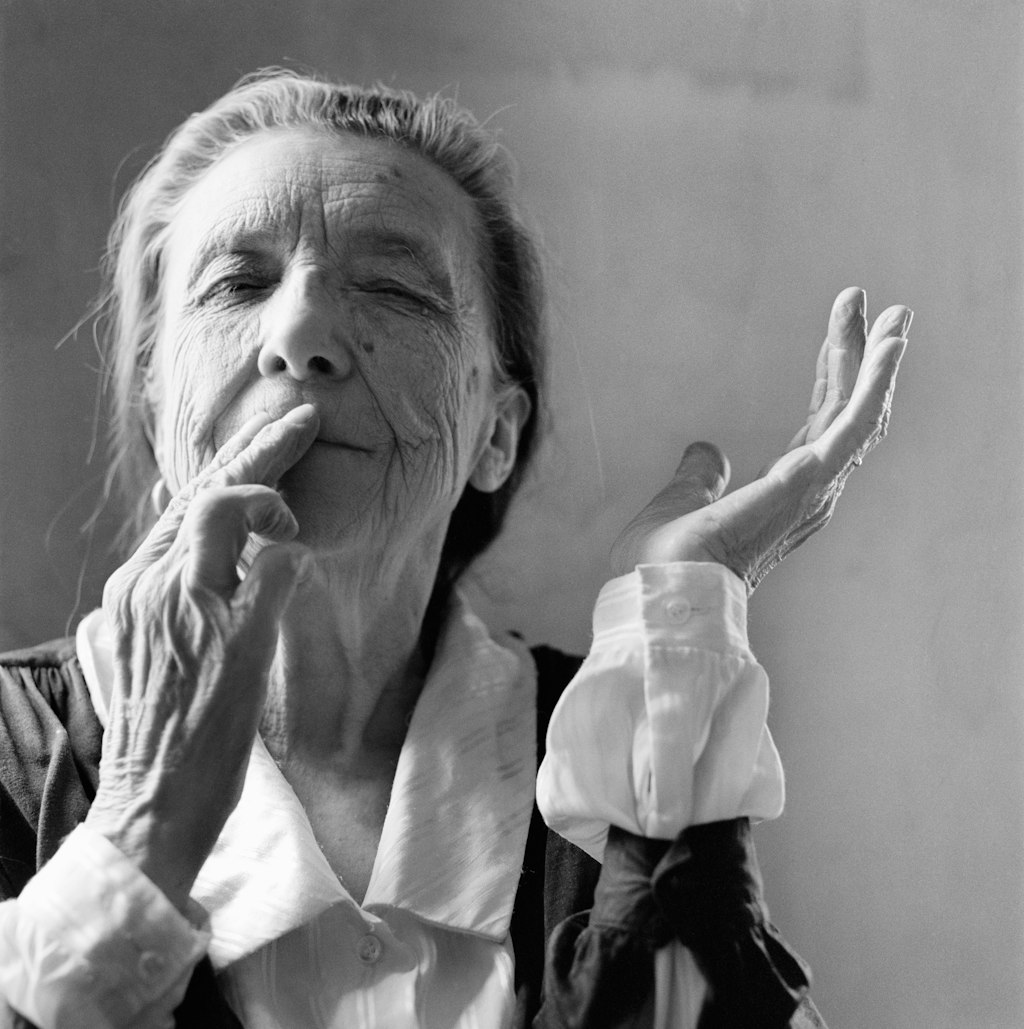

Louise Bourgeois, 1990 © Yann Charbonnier/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2023

French–American artist Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) is considered one of the most innovative artists of the past century. A prolific sculptor, painter and printmaker, she is best known for her large-scale sculpture and installation art. Drawing on her childhood experiences, Bourgeois explored a variety of themes in her art, such as family, the unconscious, sexuality and the body, and is renowned for her fearless exploration of human relationships across a relentlessly inventive seven-decade career.

Bourgeois grew up in Paris. Her parents Louis and Joséphine had a tapestry restoration business, and she assisted in the workshop by drawing missing elements in the scenes depicted on the tapestries. Bourgeois attended the Sorbonne, where she studied mathematics. At age 21, she changed her focus to art, studying at the École des Beaux-Arts, Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and at the studio of Fernand Léger, a painter and sculptor. In 1938 she married Robert Goldwater, an American art historian, and moved to New York City, where they raised three sons.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Bourgeois’s work was presented in various group exhibitions with abstract expressionist artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning. Bourgeois also engaged with European surrealists such as Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, but she was never formally affiliated with a particular artistic movement. While Bourgeois was ambivalent about identifying as a feminist, the themes of motherhood, femininity and the unconscious in her art made her a pivotal figure in the feminist art movement from the mid-1960s; Bourgeois remarked in one interview that ‘some of my works are, or try to be feminist, and others are not feminist’.

After the unexpected death of her father in 1951, Bourgeois fell into a deep depression, which led to an extended period of psychoanalysis during which time she didn’t make any new work. The work she created after this period, beginning in the early 1960s, revealed a turn toward more organic processes and forms and was exhibited in the seminal group exhibition Eccentric Abstraction in 1966, curated by American art critic and activist Lucy Lippard.

In 1980, Bourgeois acquired an industrial studio space in Brooklyn, New York, and began making increasingly large-scale work. Louise Bourgeois: Retrospective opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1982, the museum’s first retrospective devoted to a woman sculptor. She took part in Documenta IX in 1992 and, the following year, represented the United States Pavilion for the 45th Venice Biennale. In 1994, Bourgeois debuted her first large-scale Spider at the Brooklyn Museum; in 2000, she presented Maman 1999 – a steel and marble spider, which stands 9 metres high and 10 metres wide – at the Tate Gallery of Modern Art in London.

Among Bourgeois’s many honours, she received the Grand Prix National de Sculpture from the French government in 1991, the National Medal of Arts presented by American president Bill Clinton in 1997, and the French Legion of Honour presented by French president Nicolas Sarkozy in 2008.

Bourgeois continued to work until her death on 31 May 2010, at the age of 98.

-

The significance of the spider

’The friend (the spider – why the spider?) because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and useful as a spider. She could also defend herself, and me, by refusing to answer ‘stupid’, inquisitive, embarrassing personal questions.

I shall never tire of representing her.

I want to: eat, sleep, argue, hurt, destroy

Why do you?

My reasons belong exclusively to me.

The treatment of Fear.’Louise Bourgeois first depicted a spider in two small ink and charcoal drawings in 1947. It wasn’t until 50 years later, in the late 1990s, that she created the steel and bronze spider sculptures for which she is known. These sculptures range in size, with the largest reaching over 9 metres tall.

In Bourgeois’s art, the spider is a homage to her mother Joséphine. Together with Bourgeois’s father Louis, Joséphine ran the family’s tapestry restoration business in Paris. The spider, like Joséphine, is an industrious and patient spinner, repairer, weaver and fierce protector. ‘I came from a family of repairers,’ wrote Bourgeois, ‘the spider is a repairer.’ Some of Bourgeois’s spiders, such as Maman 1999, are also mothers who carry a sac full of eggs.

The spider can also be associated with the artist herself. Always making its web in relation to its body, the spider is also an artist – doing, undoing, redoing. ‘What is a drawing?,’ Bourgeois wrote. ‘It is a secretion, like a thread in a spider’s web … It is a knitting, a spiral, a spider web and other significant organisations of space.’

Bourgeois wrote that her mother was someone she would never tire of representing. In a film by directors Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach, Louise Bourgeois: the spider, the mistress and the tangerine (2008), Bourgeois described these spider sculptures as her ‘most successful subject’.

-

Artist quotes

The friend (the spider – why the spider?) because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider. She could also defend herself, and me, by refusing to answer ‘stupid’, inquisitive, embarrassing, personal questions.

I shall never tire of representing her.

I want to: eat, sleep, argue, hurt, destroy …

Why do you?

My reasons belong exclusively to me.

The treatment of Fear.

To my taste, the spider is a little bit too fastidious.

There is a very French, fiddly, overly rational, ‘tricoteuse’

side to her (Xavier Tricot), with her ever more precise and

delicate invisible mending; she never tires of splitting hairs.

This endless analysis is exhausting, and visually it can be

reductive. It makes me want to rush out onto the street and fill my lungs with air. Analyses without end, questions within questions – mincing away.

For once, this spider admits to being tired. She leans

against the wall (see the prostitute who eyes her client from the shadow of the doorway, against the door of the years).

To analyse and mince away is one thing but to make a decision

is something else (a choice judgement of value).

Caught in a web of fear.

The spider’s web.

The deprived woman.The theme of spiders is a double theme. First of all, the spider as guardian, a guardian against mosquitoes … It is a defense against evil … The other metaphor is that the spider represents the mother.

When I was growing up, all the women in my house were using needles. I’ve always had a fascination with the needle, the magic power of the needle. The needle is used to repair damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness. It is never aggressive, it’s not a pin.

I came from a family of repairers. The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it.

Art is restoration: the idea is to repair the damages that are inflicted in life, to make something that is fragmented – which is what fear and anxiety do to a person – into something whole.

The crafty spider, hiding and waiting, is wonderful to watch. The children and I would watch nature. I am not talking about the Black Spider that lives in the earth, I am talking about air spiders, tree spiders, or house spiders.

We suffered from mosquitoes. The only help was the spider. The spider is a friend.

All my work in the past fifty years, all my subjects, have found their inspiration in my childhood. My childhood has never lost its magic, it has never lost its mystery, and it has never lost its drama.

I have always had the fear of being separated and abandoned. The sewing is my attempt to keep things together and make things whole.

The bond between a mother and a child is important. It is from here that our relationship to others and the world begins.

‘The female spider’ has a bad reputation – a stinger, a killer. I rehabilitate her. If I have to rehabilitate her it is because I feel criticised.

-

Reading list

Exhibition catalogue

Louise Bourgeois: Has the day invaded the night or has the night invaded the day? Justin Paton (ed), 2023

Recommended for students ages 5+

Cloth lullaby: the woven life of Louise Bourgeois

Amy Novesky and Isabelle Arsenault, 2016

Maria Isabel Sánchez Vegara, 2020

Louise Bourgeois: Made giant spiders and wasn’t sorry

Fausto Gilberti, 2023

What the artist saw: Louise Bourgeois

Amy Gugliemo, 2022

Research library and National Art Archive

Resources on Louise Bourgeois in the Art Gallery‘s library, archive and children‘s art library

Exhibition resources

Programs

Past events

Learning program

Louise Bourgeois: Keeping my house in order Exhibition workshop for senior secondary students

Mondays–Tuesdays 10am, 12.30pm

5 February – 9 April 2024Charges apply

Online series: Online regional connect

Online regional connect Louise Bourgeois

Free, bookings required