Going platinum

Founded in May 1953, the Art Gallery Society is celebrating 70 years of Art Gallery members in 2023. For this ‘platinum anniversary’, we look back to where it all began.

Godfrey Miller Nude and the moon 1954–59 from the series Nude and the moon, Art Gallery of New South Wales, gift of the Art Gallery Society of New South Wales 1959 © Estate of Godfrey Miller

Many things happened in 1953. Queen Elizabeth II was crowned at Westminster Abbey, aged just 26. Nikita Khrushchev won the fight for power of the Soviet Union. James Watson and Francis Crick built a structural model of DNA in their Cambridge laboratory. Audrey Hepburn lit up the silver screen in Roman Holiday; and the glamour of Dean Martin, Patti Page and Frank Sinatra spilled forth from radios and into dance halls.

In the avant-garde centres of the Western art world, abstraction was taking hold, evolving from its cubist predecessors with a focus on form, feeling and gesture over representation.

In Sydney, many of the arts institutions now integral to the city were yet to be established – it would be another 20 years before the Sydney Opera House opened in 1973 and almost 40 years until the Museum of Contemporary Art was established in 1991, while the Sydney Theatre Company and Sydney Dance Company were still distant glimmers on the horizon. The art deco Sydney Trocadero dance hall on George Street hosted the uproarious annual Artists’ Ball and Art Students’ Ball, but if you wanted to see art, there were few places to go.

For those in the know, contemporary Australian artworks could be seen and purchased at David Jones Art Gallery in the Elizabeth Street department store and at Macquarie Galleries on King Street in the CBD.

The National Art Gallery of New South Wales, as it was then known, still presented works with the predominantly 19th-century pedagogical aim of raising up the uneducated masses through the preservation of classical, and decidedly British, ideals. Rather than provoking questions, the Art Gallery provided answers. The curatorial staff, which comprised solely of director Hal Missingham and his deputy Tony Tuckson, both artists, were greatly outnumbered by the board of trustees who held sway, favouring conservative, classicist works which did little to engage with the contemporary art of the day.

Missingham had taken on the post in 1945 with the proviso (as he wrote to his wife) to ‘clean the place up!’ He inherited a Victorian building, largely lacking electric and natural light and greatly in need of repair. Large 19th-century paintings strained at their frames under the weight of humidity. At the time, the trustees’ aspirations for modernisation extended only as far as the building and Missingham’s proposals to purchase Australian modernist works were met with flat refusals. But the tide was turning.

William Dargie Mr Essington Lewis, CH, Archibald Prize 1952 winner, now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra © Roger Dargie and Faye Dargie

William Dargie Mr Essington Lewis, CH, Archibald Prize 1952 winner, now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra © Roger Dargie and Faye Dargie

On 24 January 1953, with impatience at the Art Gallery trustees’ resistance to modernism growing amongst students and artists teaching at East Sydney Tech (now the National Art School), a group of around 30 art students carrying placards marched through the Art Gallery. Among them was a young John Olsen, whose sign read ‘Archibald decisions = death to art’. Over the decade following William Dobell’s controversial 1943 Archibald-winning portrait of artist Joshua Smith, the Art Gallery’s trustees had been particularly cautious in their selection of winners, as the public backlash against Dobell’s style had questioned the fundamentals of the prize. William Dargie’s realist portraits had won six times in the previous ten years; now his rather staid portrait of industrialist Essington Lewis, Australia’s wartime director of munitions, had been announced the winner of the 1952 Archibald Prize, sparking the uproar.

Sydney was changing. The population of just over 1.8 million continued to grow as new waves of immigrants from post-war Europe arrived, bringing with them new perspectives, a greater variety of cuisine and an everyday interest in the arts. The students’ January protest signs of ‘Away to Victorianism’ and ‘We’re objecting, not rejecting’ were prophetic of the changing mood.

Just over a month later, on 27 February, the exhibition French Painting Today burst onto the Sydney art scene. In a rare early win for Missingham, Sir Charles Lloyd Jones, an art collector and the most progressive of the trustees, had given the director his support to stage the show and negotiate artwork loans with French lenders. The exhibition toured throughout Australia’s major art museums and was confirmed through an agreement between the French and Australian governments.

The landmark exhibition of 123 works by 20th-century French artists, including Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Miro and Léger, sparked something for the thousands of visitors who flocked to the show, hungry for a glimpse of something fresh and in the flesh, rather than in reproduction. The vast value of the works, almost lost at sea during their treacherous voyage and much reported in the press, also proved an enticement. Over the month-long exhibition in Sydney, 150,000 people visited the show and nearly 16,000 catalogues were sold, making it one of the Art Gallery’s first blockbuster exhibitions.

Just six weeks after the exhibition closed, around 300 people gathered at the Art Gallery on 12 May 1953 to form a body of friends to support the growth of the institution, and the National Art Gallery Society of New South Wales was founded.

Building on the momentum of the show, Sir Charles Lloyd Jones had revived his own 1942 call for a membership body – an idea which had been percolating since 1933. Twenty years on, BJ Waterhouse, president of the board of trustees, welcomed the suggestion from Sir Charles and Professor EG Waterhouse. Chief Justice Kenneth Street, the first president of the Society, called the meeting into session, expressing a hope to ‘provide a link between the gallery and the public’. The following day, The Sydney Morning Herald reported, ‘The Chief Justice said the society would not be for artists alone; laymen would take a big part. It would not advise the trustees, but would cooperate with them and help them to bring the gallery to the public.’ Emphasising the Art Gallery’s remove from the bustle of the city in the expanse of the Domain, the article noted the need for some ‘special attraction’ to remind the public of ‘the pleasure that aesthetic appreciation could give’.

The Art Gallery Society of NSW was incorporated as a company limited by guarantee in July 1957, and the Chief Justice remained the Society’s president until his death in 1972. Alongside him on the 1953 founding council were businessman Milton Atwill (who chaired meetings in Street’s absence), honorary treasurer Frank Elliott Trigg, honorary secretary David Lloyd Jones and a further 18 members, including artist Weaver Hawkins, antiques dealer Stanley Lipscombe, Hanne Fairfax (second wife of newspaper magnate Sir Warwick), Dame Helen Blaxland and fashion editor of The Australian Women’s Weekly Mary Horden. In 1954, artist Lyndon Dadswell and Vincent Fairfax both joined the council, with Fairfax appointed chairman. Missingham and Tuckson sat on council ex officio.

Founding members included a number of Sydney society’s elite as well as leading artists of the day. Amongst the group: five members of the Fairfax family, Frank Packer (as yet to be knighted) and his first wife Gretel, chairman of the ABC Sir Richard Boyer, collector Norman Schureck, art historian Bernard Smith, publisher Sam Ure Smith, art critic Paul Haefliger and artists Judy Cassab, James Gleeson and Desiderius Orban.

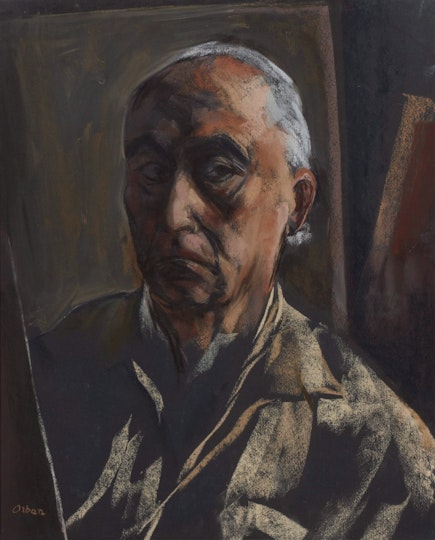

Desiderius Orban Self portrait 1954, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Estate of Desiderius Orban

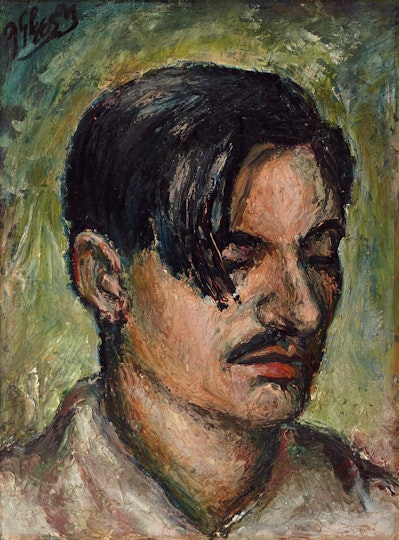

James Gleeson Self portrait c1941, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Gleeson O'Keefe Foundation

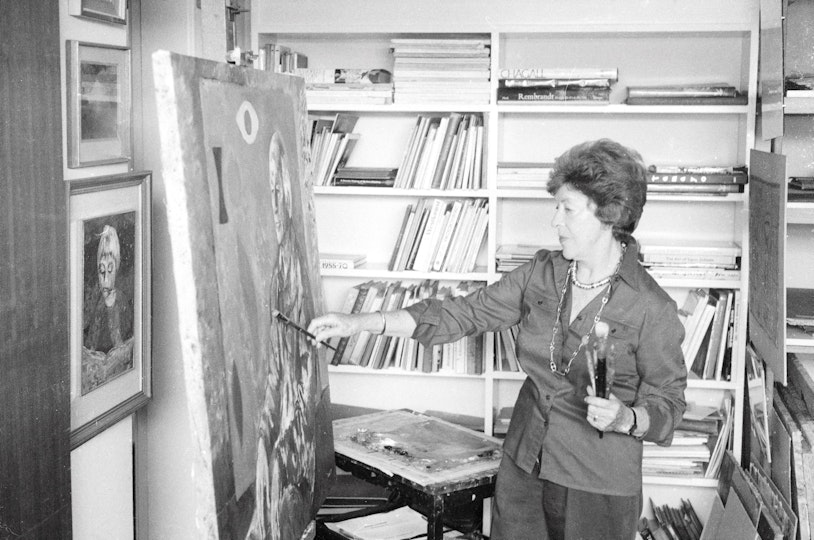

Judy Cassab in her studio, 1987–88, photo: Robert Walker, Robert Walker archive, National Art Archive, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Estate of Robert Walker

Right from the beginning, the Society held engaging and innovative event programs, transforming the Art Gallery’s offering for the public. For its first function, on 28 July 1953, it screened two films, on the artists Albert Namatjira and Maurice Utrillo. That September, a ‘Gallery week’ was held by special arrangement with management and the Art Gallery was kept open until 9pm each night so visitors could take in lectures and enjoy an exhibition of Australian art from Glover to Drysdale. So impressed was the NSW Government with the Society’s initiatives that it awarded the organisation a grant of £2000 to continue its work.

In 1954, lunchtime promenade concerts in the Art Gallery began, programmed by Eugene Prokop of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and Tuckson began leading guided tours for Art Gallery members. Art lectures by Missingham, Bernard Smith, artists Roland Wakelin, James Gleeson and Douglas Dundas, and architect Robin Boyd sparked an enduring lecture program, becoming monthly in 1955, with an emphasis on engaging members through art appreciation. Volunteers helped to coordinate and run events. From 1957, the Society ran a regular cinema program and film became an important part of Art Gallery programming. When the Society bought the Australian rights to Le mystère Picasso in 1962 and showed the film at the University of Sydney’s Union Theatre, more than 15,000 people came to see it.

Raucous parties, such as the first ‘concert by candlelight’ in the Grand Courts in 1955, added sparkle for members, but lessened the organisation’s appeal for Missingham, who had been an early champion of the group. Outraged to find champagne and chicken dinner on the Art Gallery’s floors the morning after the concert, and appalled by councillor Mary Horden’s rearrangement of the French tapestries which were on display at the time, he withdrew his membership. Cleaners were organised for future events and apologies issued. The following year the ABC began broadcasting the concerts on radio, later contributing to performers’ fees.

At a council meeting after the event, Missingham put forward the priorities the Art Gallery trustees wished the Society to pursue: assistance with the funding of a library and electric lighting, as well as the publication of a quarterly magazine, as the institution did not have the resources to produce this itself. Funds raised from Society events could assist with these and other much-needed changes, while Society programs could help enhance visitors’ experience and public awareness of the Art Gallery. This would be the role of the Art Gallery Society for the next 70 years.

Left to right: Lorna Nimmo, Tony Tuckson, Peter Dodd, Hal Missingham and Ormond Bisset after an Art Gallery Society lecture, c1957, National Art Archive, Art Gallery of New South Wales

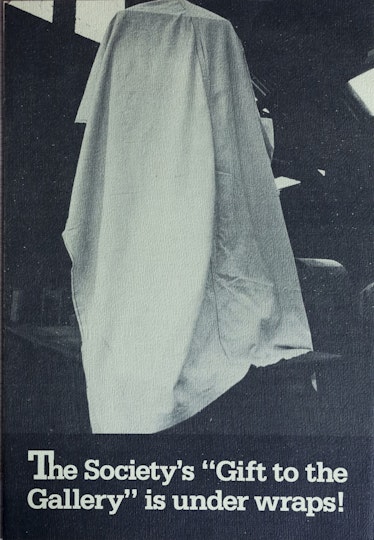

An Art Gallery Society preview for the exhibition Fabulous Fashion, which travelled from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, was held on 13 August 1981. The program details a French banquet finished with cognac and cigars

By the time the Art Gallery Society was incorporated as a charity in 1957, membership programs had contributed to the lighting of the foyer, to the library and to conservation works. The first issue of the Art Gallery’s Quarterly Bulletin, edited by Missingham and funded by the Society, came out in June 1958. An early precursor to Look, all members received a free copy of each publication. By 1959 the councillors reached their goal of 2000 members, and the Society proudly presented its first gift of an artwork for the Art Gallery’s collection. Nude and the moon 1954–59 by New Zealand–born, Sydney-based modernist Godfrey Miller is a multi-faceted abstraction of seemingly iridescent planes, both mystical and calm. Combining Eastern and Indian cosmological thought with cubist ways of seeing, the work encapsulates the artist’s philosophical vision of cosmic unity.

Seventy years on from that first May meeting, over 255 artworks have been purchased for the collection by the Society and more than 33,000 members enjoy being a fundamental part of the Art Gallery. Miller’s modernist, shimmering work feels apt in this ‘platinum’ anniversary year. Beyond its silver form, the painting, made by a local artist in a modern language of abstraction over the course of those first few years of the Art Gallery Society, speaks of the role Art Gallery members have played in fostering and shaping a modern Art Gallery for New South Wales.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine