Life’s a beach

Louis Nowra considers how artists have captured the transformation of Sydney from convict colony to waterfront paradise.

Charles Meere Australian beach pattern 1940, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Estate of Charles Meere / Copyright Agency

Often it takes a newcomer, and not a local, to fully appreciate a city’s beauty and its flaws, its social character and hidden gems. When I came to Sydney in the late 1970s my first impressions were dictated by comparisons with my hometown of Melbourne. The bleak sky was replaced by dazzling light, the sandstone buildings with their warm changing colours were beautiful, compared with the southern city’s cold bluestone. Then there were the monumental, even spooky fig trees, Sydney’s winding unruly streets, the gorgeous harbour and, of course, the architectural and engineering marvels of the Harbour Bridge and Opera House.

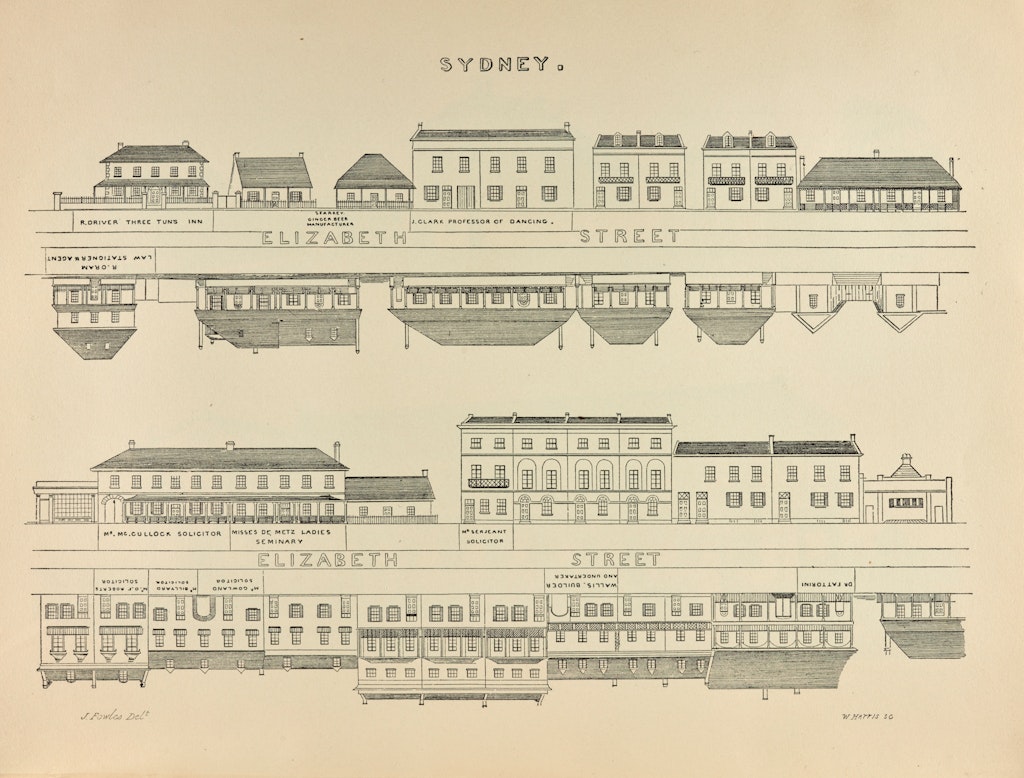

My recent book Sydney: a biography was my attempt to try to explain to myself why I fell in love with the city. During my research I realised there was plenty of written material but I gravitated towards pictorial representations, wanting to find out how Sydney saw itself over the years. There were contemporary sketches of the early settlement by the convict artist Thomas Watling that revealed, more than words could, a village struggling to permanently exist. Joseph Fowles’s drawings of a young city full of elegant Georgian buildings was a proud account of how far Sydney had progressed over the first 60 years of its colonial existence.

Joseph Fowles Historical exterior view of Clark's Assembly Hall on Elizabeth Street in 1848 from a 1962 facsimile, National Art Archive, Art Gallery of New South Wales

During the same years John Rae, an amateur artist, described the same city in a wonky social realist style as a place of scattered sandstone buildings surrounded by a desolate Hyde Park and the torpid atmosphere of the ramshackle George and Pitt streets.

These works couldn’t be more different from those of Conrad Martens, the colony’s first professional painter. He earned money undertaking commissions for the wealthy and portraying their mansions and villas in an enchanting, picturesque style. The houses in their solitary splendour are stately bastions of civilisation, imperious and serene, as if they exist in an Arcadian paradise.

Conrad Martens View of Sydney Cove 1848, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Martens’ romantic works would reach their ultimate realisation years later in Brett Whiteley’s lyrical, even kitsch evocations of the harbour. It was only in the late 1890s that artists portrayed another Sydney, with two of the most important artists coming from Melbourne.

Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton camped near Mosman and set about painting the city and its harbour through the eyes of newcomers. Both had been prominent members of the Heidlberg School, with its bush settings and male-orientated visions of Australia. In Sydney their works changed. The exquisite harbour with its glittering waters and hazy briny atmosphere mesmerised them, as did the beaches of Manly and Coogee, as did the light of an infinite blue sky. So influential were their works that it was said of Arthur Streeton that it was he, rather than Governor Phillip, who ‘was the first discoverer of Sydney Harbour’. The cerulean hue of his Sydney sky and sea would take his name, Streeton Blue.

But it was the arrival of modernism during the 1920s and 30s that changed the way Sydney saw itself, this transformation aided by the symbiotic relationship with the gradual construction of the Harbour Bridge. For artists, the bridge represented a new era, the 20th century’s rejection of the duncoloured realism of much Australian painting, and a bold reimagining of how to view cities as centres of modernism.

Two women artists were especially attracted to this mighty structure, Grace Cossington Smith and Dorrit Black. Smith savoured the curves of the bridge and how it reflected the undulating nature of Sydney itself, and its two soaring arches designed to meet and meld into one giant arch; all of this rendered in planes of vivid colours, not unlike the fauves.

Black’s The Bridge 1930 (in the Art Gallery of South Australia collection) is a portrait of industrial dynamism, with an almost spiritual aura rendered in pale greens, blues, greys and ‘shimmering peacock’. The bridge, yet to meet in the middle, is like two mechanical animals leaping in slow motion at one another. It’s a monument to modern engineering, with a five-mast clipper, anchored under the growing bridge, a memory of another, older Sydney to which Black was saying goodbye.

Brett Whiteley The balcony 2 1975, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency

Tom Roberts Holiday sketch at Coogee 1888, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Arthur Streeton Beach scene 1890, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Grace Cossington Smith The curve of the bridge 1928–29, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Estate of Grace Cossington Smith

The photography of the era was even more interesting for the way it pictured Sydney. In contradistinction to Melbourne’s gloomy realism and grim socialist outlook the photographers understood that Sydney was individualist, highly sexual and pagan. These photographers discovered the primal sensuality and potency of life on Sydney’s beaches.

Perhaps the most influential were a husband and wife, Max Dupain and Olive Cotton. Dupain’s archetypal men are intensely physical, each muscle straining with concentrated effort, as in his Discus thrower c1939 (in the National Gallery of Victoria collection), where a naked man is caught in a swirling action of hurling his discus, as though embodying the spirit of the ancient Greeks.

Olive Cotton ‘Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind’ c1939, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Olive Cotton ‘Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind’ c1939, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Perhaps one of Cotton’s best photographs is one taken in 1939, ‘Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind’. It’s an image of a beautiful swimwear model shot from the side, only her shoulders and head showing. She’s facing a gentle sea breeze, which wafts over her youthful skin, her eyes shut as in a state of bliss. It’s a beguiling and sensual image of a contented woman, at one with nature, the sun, sea and sand. It’s hard to think of another photograph that so aptly sums up a paganism that attains a quasi-religious epiphany.

If Dupain’s photograph has become an ‘iconic’ image of our beach culture, then so has Charles Meere’s painting Australian beach pattern. This 1940 work encapsulated the trend to mythologise Sydneysiders’ pagan way of life as symbolised by the beach.

It depicts an action-packed family day at a sunny beach. It’s both strange and familiar, and even to some, eerie, and over the years has been the focus of many a fervid interpretation. The painting is a tableau of beachgoers, done in a classical tradition, whose athletic perfection reaches such monumental heroic proportions that it almost verges on the satirical.

But it’s no wonder that this is one of the most popular paintings in the Art Gallery of New South Wales. These tanned men, women and children on a Sydney beach are gods in bathers. The irony is that this was painted by an Englishman.

Louis Nowra is a Sydney-based novelist, playwright, screenwriter and librettist. He will deliver an Art Appreciation lecture, titled ‘Making Sydney a modernist paradise’, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales on 1–2 May 2024.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine